by Annabelle Berríos

Paisagens Itinerantes

Travelling Landscapes

5 MIN | Magazine 39

“O que é herdado não é roubado”

Puerto Rican saying

Apresentando-me

My sister Ivette, 21 years my senior, bragged about how she chose my name, saving me from the sour fate of being named Ana María.

“Por amor de Dios, how many Marías?,” she exclaimed, rattling off the names of my sisters: “Ivette Maria, Maria Margarita,” and finally “José,” my brother’s and father’s name. “I told our mother: ‘Basta with the Holy Family! Annabelle, her name has to be Annabelle, spelled the French way with two l’s and an e at the end.’”

With that, Ivette raised a glass of white wine in my direction, concluding with: “You are welcome.”

Annabelle comes from the Latin word amabilis, or amable in Spanish. Growing up Catholic, I assumed that amable was about earning love and affection through agreeableness (which could be faked in order to protect contrarian sensibilities). As an adult, I learned that amable means friendly and kind, attributes that require courage, sincerity and open heartedness for their embodiment. My last name, Berríos, is a variant of the Spanish word barrios – neighborhoods outside the city- which I have tended to regard as those informal networks that exist on the borderlands of memory and visibility.

I was born in the archipelago that the Taíno named Borikén, which translates to: “The great land of the valiant and noble Lord.” The Taíno were the primary inhabitants until the arrival of the Spanish in the late 1400s. Dating back to the time of Spanish colonization, the islands are now collectively known as “Puerto Rico,” meaning “rich port.” I moved to the mainland United States, motivated, in part, by what I now recognize as modernity/coloniality: a collective, misguided and harmful narrative of progress and success. The part of me that sought alignment with more progressive values led me to California, a peninsula named after the fictional Calafia (1), a pagan Queen who ruled an island of warrior women and fought the conquest of Christianity.

A few weeks ago, I found myself a guest in a quiet town near the border separating Portugal and Spain, in the Algarve. Recently, I learned through DNA testing that I have both Portuguese and Spanish ancestry in significant percentages.

My mixed ancestry also includes indigenous Taíno and African, among other ethnicities. Weary of the “live to work” ethos of the United States as well as pandemic isolation, I planned a longer visit to slow down and notice the interplay between inner and outer ancestral landscapes.

(1) The origin is a Spanish romantic novel from 1510 called Las Sergas de Esplandindán.

Diálogo entre paisagens

I tend to introduce myself to a new place by describing my default inner landscape, which in my case is tropical. Generally sunny, my coastal landscape is prone to quick sorrowful thunderstorms that give way to optimistic rainbows. At the Algarve, in a farm remembered by its olive trees, it was a bamboo bush that first greeted me, rustiling when I passed by, whistling hello. I felt it simultaneously as the caress of a cool breeze and the warmth of contactless presence. I noticed how the wind spoke through the wind tunnels formed by the canes, making me wonder – who was speaking? Every night, I visited the bamboo bush, feeling the shudder of a shared wind.

Like me, bamboos don’t do well in still water: we need appropriate drainage. We also don’t like our roots to get cold. In the silence of a quiet farm, dreams brought up to the surface some of what asked to be drained out. In the dream world, I saw myself riding a train in the wrong direction alongside the coast. Oddly enough, there was a small train station a short walk from where I was staying, with a gentle, haunting horn that sounded like a holdover from my dream. I usually heard it when I was sitting in the living room sipping tea, nibbling marble cake. While I could not see the train, I could see – thanks to floor-to-ceiling windows – the Ponte Internacional do Guadiana stretching across the Chança River to connect Portugal and Spain. I longed to cross it.

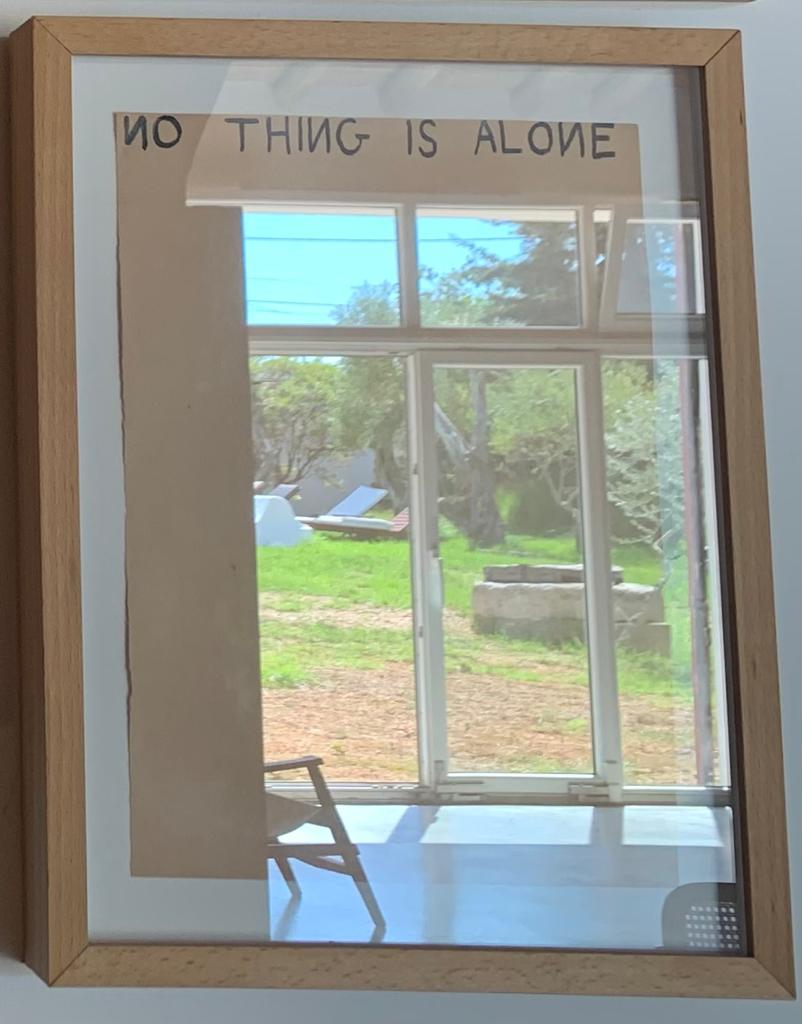

During my first few days, patterns of shadows and reflections captured my attention. My iPhone camera lens aimed to depict patterns of interdependence through photographing mirror images.

There was a welcoming presence in the farm, a nonhuman togetherness or companionship that was palpable in the spaciousness. However, there is also no denying the hearth of the human hearts that opened ours along the way: Portuguese, Colombian, Cape Verdean and Brazilian.

Venturing out into the surrounding towns, I noticed other patterns in the landscape: clusters of medieval city or castle walls, cobblestone alleys, and churches in close proximity to one another, bordering bodies of water, such as the Gulf of Cadiz, the Gilão River and the Ria Formosa Natural Reserve. I noticed how the medieval city walls I was seeing in the Algarve activated body memories of the City Wall of Old San Juan, in Puerto Rico. I recalled standing inside the threshold-tunnel of The Gate of San Juan, which separates the Bay of San Juan from the Cathedral of San Juan, a place to breathe and consider the influences on each side of the wall without being defined by them. The Wall of San Juan also marks a boundary between the old city and the new city that grew past the wall. I was born in the new part of the city, but feel drawn to the bohemian aspects of the old city, even when repelled by structural reminders of colonialist occupation, and crowds of tourists from the cruise ships.

Looking down from the Castelo de Tavira, I was struck by the close proximity of private homes to archeological remains – sometimes even appearing to share a wall – making them seem inextricably intertwined with one another. There is a future Phenician – Turdetanian museum emerging from the ruins of a medieval residence that is still being excavated, across the street from what appear to be private homes. The past and the present are not discernibly separate – they appear to grow together, like conjoined twins.

I considered this within my own body, that there are paradoxes within landscapes that have to find a way to relate to one another if the larger organism is going to manifest harmony and kindness at full potential. I sensed the value, not only of having visible reminders of past structures, but also of noticing the values that those structures embodied, because they are intertwined – although perhaps not as visibly – with how life is lived today.

I reminded myself to breathe and feel. Thunderstorms and rainbows need air and water.

“That we close down is not a problem. In fact, to become aware of when we do so is an important part of the training. The first step in cultivating loving-kindness is to see when we are erecting barriers between ourselves and others. Unless we understand-in a non-judgmental way-that we are hardening our hearts, there is no possibility of dissolving that armor. Without dissolving the armor, the loving-kindness of bodhicitta is always held back. We are always obstructing our innate capacity to love without an agenda.” ~Pema Chodron

In Cacela Velha, while I delighted in the short boat ride crossing Ria Formosa, I noticed with joy and tenderness the locals who opted to make the crossing back by foot, given the low tide. I watched the backs of families, the water at times reaching their waists, laughing as they held bags over their shoulders, attentive, I presumed, to the elevation under their feet and the movements of the water, zig zagging the distance between the island beach and the shore.

Belonging is much more satisfying than control.

E agora, a mudança de formas em progresso

Back in the United States, I accept that the insights from the journey are still in transit, existing as fragments, voices, echoes, feelings, sounds and smells that need time and space to shape their own stories. To help me embrace disorientation on dry land, I gaze at the calçada portuguesa of Cascais, which mirrors the patterns of the waves of an unseen, unpredictable yet ever present Atlantic Ocean.

And… to the Maria on the altar in my home in California, the Mexican Maria known as Guadalupe, previously revered as the Aztec Tonantzin, I pray for courage to embody kindness in the borderlands of paradox.

A few weeks ago, I found myself a guest in a quiet town near the border separating Portugal and Spain, in the Algarve. Recently, I learned through DNA testing that I have both Portuguese and Spanish ancestry in significant percentages. My mixed ancestry also includes indigenous Taíno and African, among other ethnicities. Weary of the “live to work” ethos of the United States as well as pandemic isolation, I planned a longer visit to slow down and notice the interplay between inner and outer ancestral landscapes.

Annabelle Berríos

MA, JD

Shapeshifter. Weaver, connector, and bridge builder. Writer inspired by terrapsychological and postactivist inquiry. Social impact consultant and coach. Can be reached at annabelle.berrios@gmail.com. Forthcoming website at: www.umbralconsulting.com